Monday, December 27, 2010

Three Little Indians

Sunday, December 19, 2010

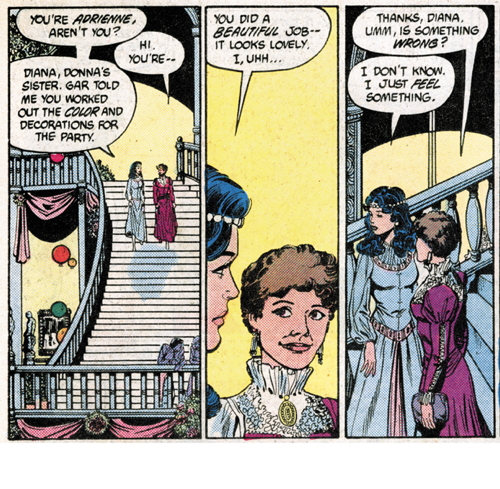

Adrienne Roy

Adrienne Roy died last week after a year long fight with ovarian cancer. She was only 57.

A favorite of the convention circuit, beloved by those editors, writers and other artists who worked with her, not to mention her family, the list of memories invoked by those who knew her is both illuminating and touching.

You should read them, and all about Adrienne while you are at it.

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

Death by a Thousand Cuts

Before we got into playing, Chuck and I got into a bit of a discussion on superheroes and killing. It's an old debate, and a good one, and Mike was good to rein us in as we could have gone on for hours. Chuck's basic position, and it's a very understandable and common one, especially among players of superhero games, is that superheroes who swear they don't kill are being pretty naive and weak. When a criminal psychopath like the Joker has demonstrated his ability to escape from confinement time and time again, each time murdering dozens before being recaptured, only for Batman to defeat and not kill him, Batman must share some culpability for the Joker's crimes. The superhero who swears off killing is not only weak and ineffective, he's kind of a dope.

On my side, I tried to argue that while this argument makes a lot of sense on a visceral, "He killed so I can kill him" level, superheroes like Batman, Captain America, and the X-Men (all of whom are generally portrayed as No-Kill-Heroes, despite many notable exceptions to this rule) use their no-kill philosophy to teach us something: Just because someone else is evil, does not justify your own descent into evil to defeat them. Captain America has given this speech a hundred times if he has given it once. To execute an evil man is to lower yourself to his level. The superhero is a self-appointed agent of criminal apprehension, not a judge or jury. If a criminal is to be executed, that will be determined by a jury of his peers, not one man, no matter how justified that execution might appear. This is not weakness, it is a recognition of the essential character of the American criminal justice system. It's not Batman's fault that the Joker kills people. Batman does his part. That doesn't mean he doesn't feel guilty when the Joker kills. Of course he does. When the Joker killed Robin with a lead pipe, Batman wanted to kill him. But that would also be murder. Because Batman is not empowered by the American people to hand out sentences of execution. That right is reserved, not for Batman, Captain America, or the X-Men, but to you and me. We are the ones who decide if people live or die. And letting Batman do it for us is taking the cheap way out.

But in many ways, what is more interesting here is the long debate over superheroes and killing, which has been portrayed in many wonderfully thought-provoking books over the years. Chuck mentioned a panel from X-Men, and it is a famous one, so I thought I would represent it here and you saw it at the top of the page. Wolverine murders a guard in the Savage Land while Storm and Nightcrawler look on, the former saddened and the latter horrified. Claremont and Byrne are demonstrating their genius here, because it takes a thoughtful creative team to move the camera off of the murder and onto the reaction shot. Jim Lee would have kept the camera on Logan as he stuck his claws through this guy's back. Yawn. You see one merciless killing, you have seen them all. But the reaction shot illustrates the real drama of the scene. It's not the killing, it's the moral and ethical questions the killing raises. That's what makes this story so damn good.

Lethality in comics has gone on big pendulum swings through the decades. In the Golden Age, no one batted an eye when the bad guy got killed. By the 1960s, however -- and I am tempted to say this was largely the result of the Comics Code, but I may just be taking the easy way out -- Superman had become the Blue Boy Scout and even Batman was having his goofy period. When Wolverine killed in the pages of the X-Men it created tension and a moral quandary which built for a while, peaked, and finally collapsed by the 1990s. Later writers tried to portray this split in comics; the Avengers ended up splitting into two teams when one half (led by Black Knight) decided to kill the Kree Supreme Intelligence and the other half (led by Captain America) refused to. But really this was all just the pitiful thrashings of a crippled giant. Marvel was deep into its darkest days by this period, and it seemed as if every hero and team was now carrying guns and wearing armor. Don't tell me you have forgotten Fantastic Force. When a superhero team founded on principles of exploration, imagination, and adventure has been turned into a Rob Liefeld book, you know you have gone far off the reservation.

The reason that cover looks so crappy, by the way? Foil. Nuff said.

These days, even Captain America kills. It is, after all, war. And no one should mistake me for some kind of super-pacifist who wants to trash any superhero who kills. That's not my point at all. Rather, I am mostly interested in a good story. And tension -- between those heroes who kill, and those who do not -- makes great story. In order for that tension to work, both heroes have to have some kind of authority. They have to be successful at what they do. If only one of those two approaches works, then obviously it is the only correct one and the tension evaporates. We need more panels with Storm and Nightcrawler cringing as Wolverine murders a guard. That's great comics.

But, in the end, neither of these approaches succeed. At least in comics. It doesn't matter if the Batman kills, or Captain America kills, or even if Wolverine kills, because Batman, Captain America and Wolverine have to appear in comic books every month, and every story requires more antagonists, more evil men who deserve killing. Put the Joker in prison and he escapes. Kill him and he just comes back from the dead. Ultimately, both approaches are doomed to failure. The comic book superhero will never bring justice to the city ... until his book is cancelled. See James Robinson's Starman.

More soon. I am teaching an upper division English course at UCR next quarter on graphic novels and comics, and a course in the spring on the superhero narrative. So you will see a lot on these pages about those courses. You may even be one of my students!

Friday, November 19, 2010

Field Guide to Superheroes, Volume 2

The first piece of the Field Guide has gotten us all great reviews both from RPGNow and from Steve Kenson, the creator of ICONS, who you can hear on the latest Vigilance Press podcast. Now that I am back in town, I am working furiously on the final edits for Volume 2, which will add ten more archetypes and complete the first half of the project.

The first piece of the Field Guide has gotten us all great reviews both from RPGNow and from Steve Kenson, the creator of ICONS, who you can hear on the latest Vigilance Press podcast. Now that I am back in town, I am working furiously on the final edits for Volume 2, which will add ten more archetypes and complete the first half of the project.- The Descendant is a hero who has inherited his title from an older hero who has died, lost his powers, turned to evil or retired. This gives the new version a history, but also big shoes to fill. He may have started off as a Sidekick.

- The Divine Hero is a character whose powers stem directly from a living religion like Christianity, Islam, or Judaism.

- An Embodiment personifies a universal force, such as Justice, the Earth, or Speed. He or she is very powerful but also has to answer to an even more powerful boss.

- The Ex-Con is a former villain or petty criminal who now fights crime. He may be a good guy who got mixed up with the wrong crowd or a real scoundrel who is working for justice only under duress.

- The Femme Feline is an especially popular sort of Animal Hero. A woman with a cat motif, she is morally ambiguous and flirty.

- The Feral Hero is a Jeckyll & Hyde character who tries to do good but struggles with a dark, animal nature which leads him to kill.

- The Focused Hero is a normal person with one super-power – such as flight, invisibility or great strength -- which he has learned to master.

- A Gadget Guy or Gadget Girl is usually a scientist with a collection of weapons and other equipment, including a vehicle.

- The Handicapped Hero overcomes a serious disability through advanced training, superpowers, or just raw guts.

- The Jungle Hero is a Tarzan-style hero who is caretaker of a hidden land and who often has animal-related powers

Thursday, November 18, 2010

"Comics & the Graphic Novel in America and Britain"

So a couple days ago I got a call from Deborah Willis, who is Department Chair in English at UCR now but who I will always remember as the woman who taught me Marlowe, and she asked if I would like to teach a class on, well, pretty much anything I wanted. Ordinarily I am kind of a dope when offered awesome things, but this time I had the sense to say yes. The course number we are using is supposed to be 20th century American and British lit, and she suggested something on graphic novels, so I put those two ideas together and decided to do half the class on American creators and the other half on British creators. UCR has 10 week quarters, so our reading list is painfully short. It was easy to come up with the British half: Moore, Gaiman, Morrison and Ennis gave me a great cross-section and every one of them are amazingly talented, active, and accessible.

So a couple days ago I got a call from Deborah Willis, who is Department Chair in English at UCR now but who I will always remember as the woman who taught me Marlowe, and she asked if I would like to teach a class on, well, pretty much anything I wanted. Ordinarily I am kind of a dope when offered awesome things, but this time I had the sense to say yes. The course number we are using is supposed to be 20th century American and British lit, and she suggested something on graphic novels, so I put those two ideas together and decided to do half the class on American creators and the other half on British creators. UCR has 10 week quarters, so our reading list is painfully short. It was easy to come up with the British half: Moore, Gaiman, Morrison and Ennis gave me a great cross-section and every one of them are amazingly talented, active, and accessible.- Scott McLoud, Understanding Comics

- Will Eisner, A Contract with God

- Jaime Hernandez, Love & Rockets: The Girl from HOPPERS

- Frank Miller, The Dark Knight Returns

- Gail Simone, Welcome to Tranquility

- Neil Gaiman, Sandman: Dream Country

- Garth Ennis, Hellblazer: Damnation's Flame

- Alan Moore, V for Vendetta

- Grant Morrison, All-Star Superman

Thursday, November 4, 2010

Quick Plug for Usagi Yojimbo

I first discovered Usagi Yojimbo as an undergrad, and I have to admit that when I first read it I considered it something of a guilty pleasure. I mean, this is a comic about a rabbit. It felt ... so childish to be reading a comic about a rabbit. Except, of course, that the comic is "about a rabbit" to the same degree that Maus is "about mice." Which is to say: not at all.

I first discovered Usagi Yojimbo as an undergrad, and I have to admit that when I first read it I considered it something of a guilty pleasure. I mean, this is a comic about a rabbit. It felt ... so childish to be reading a comic about a rabbit. Except, of course, that the comic is "about a rabbit" to the same degree that Maus is "about mice." Which is to say: not at all.Thursday, October 28, 2010

Vigilance Press Podcast

I had the real pleasure last night of participating in a podcast with Mike Lafferty (the self-described "Stephen Wright of gaming"), the highly-entertaining and wonderfully talented Dan Houser, and the distinguished Charles Rice, President Emeritus of Vigilance Press. We talked about ICONS, a relatively new superhero RPG system with a rules-lite, fun-heavy approach.

You should check it out.

ICONS is the platform for my Field Guide to Superheroes project. I began work on this about eleven or twelve years ago while studying at UNLV and I initially had the help of Darren Miguez, a good friend and fellow comics nerd who is now off corrupting the minds of children from behind a librarian's desk in New Jersey. At the time, Champions was pretty much the only RPG out there for playing superhero games, and although I played Champions and its related games throughout my college years, I was tired of watching the eyes of my players glaze over whenever I tried to teach the game. And Champions has only gotten more fine grain over the years, so I feel fairly justified in my desire for something which was more intuitive, which beter simulates thie high-speed and energy of superhero comics, and something which is just plain easier to play. When even Ken Hite calls Champions, "the best game I never learned how to play," I know I'm on to something.

Anyway, my idea was originally for a diceless superhero RPG system, but while I was working on that I started coming up with a long list of superhero archetypes. Many gamers have worked up superhero archetypes since then, and I don't especially claim to be doing anything new, but my approach was different than other authors. I did not want to categorize heroes by their powers necessarily; I wanted to work with story role instead. So, for example, my archetype list did not -- and still does not -- have entries like "Strong Guy" or "Speedster". Because, to my eye, the powers the character has are less important than how he got them or what kind of stories he appears in. That "Strong Guy" could be an Alien Hero like the original Superman, a Mythic Hero like Gilgamesh, or a Spin-Off Heroine like She-Hulk, and the fact that he's from another planet, thinks he's a god, or is a female version of a male hero is far more important than the fact that these heroes just happen to be strong.

Eventually I settled on 40 Archetypes -- not because that's all there is, but because I had to stop somewhere -- and spent a page or so talking about each one. To illustrate the project, I filled it with black-and-white con art depicting all our favorite examples of these archetypes. For this, I owe the internet. And in this state the Field Guide saw a lot of use. Whenever I ran a superhero game, I trotted out the Field Guide to help new players get character ideas. When I helped organize and GM for Crucible City MUX, an online RPG for the Mutants & Masterminds system (now long closed), these archetypes became a game feature. And, since M&M also happened to be a pretty darn good superhero RPG, my need for a system of my own was happily resolved.

About five years ago I set out to publish the Field Guide for M&M. I made up a sample character for each archetype, 40 in all, and in the process created a superhero setting which I call Worlds of Wonder. But, again, the real stumbling block here was the art. I certainly could not use all the internet sketches I had downloaded in the real book! Emboldened by the success of Escape from Alcatraz, I got Bill Jackson to do some pieces for the Field Guide, but it was just such a large project, and I had so many other things going on at the time -- like a dissertation -- that it fizzled out and never was completed. And there the Field Guide sat for years while I finished my degree and became a Doctor of Comics.

When ICONS came out it didn't at first get much notice from me, because I am in the middle of a D&D 4E campaign and I don't expect to have time to run anything else for about a year. And if I was going to run something, it would probably be M&M, which I love, and which worked out so very well in my 2008 POTUS campaign, also in the Worlds of Wonder setting. But Chuck started talking ICONS up to me, and what I realized is that this is a game that doesn't have a whole lot of support already. When I was working up the Field Guide for M&M, Phil Reed had already done dozens of more traditional archetypes (Strong Guy, Speedster, etc.) for the system. But here there would be no competition. I had the opportunity to get into a game on the ground floor. Which is very cool. Then I read the game, and realized it was based on FATE, which I have wanted to work with for a while. And then, after I turned in the first part of the manuscript and Chuck recovered from his, "This is FIFTY PAGES!" moment, he told me Dan was doing the art. This is very, very good news because -- as you have picked up by now -- I can't draw and with Dan involved I knew I'd be getting someone who understands comics, their artistic history, and who would be instantly recognized as the ICONS house artist. When people look at the Field Guide, it will be familiar to them. It will look like ICONS.

The first volume of the Field Guide covers the first 10 archetypes (Alien Hero through Defender) and a good chunk of the Worlds of Wonder setting. It's got 10 fully developed characters suitable for PCs or NPCs, and they all have plot hooks so they're useful to the GM. I've had enormous fun writing the Field Guide, it's been such a useful reference for me when I run or play superhero games, the setting has been tested to success in more than one campaign over the years, and I cannot wait for you all to see it.

My thanks to Chuck, Mike and Dan for giving me a chance to do so.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

The Morning After Magicians

My good friends and regular D&D partners celebrated a birthday with a trip to an Indian reservation and a 12-hour peyote trip, which led to a mystical experience involving aliens, telepathy, and "rolling" states of altered consciousness which I cannot help but -- in at least a small way -- envy. For while I study and read and write about magic and magicians, and no doubt will continue to do so till the end of my life, I will never perform a magical working for the simple fact that I'm too square to do drugs. When I left home, and my Dad packed up all my belongings and drove me to my college in another state, he had only one piece of advice for me, and it was "Stay away from drugs." So I have. I'm that kind of guy.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

"The Last Great Work of Alan Moore"

The last 24 hours have seen an outpouring of sympathy and, I imagine, scorn over the folding of Wildstorm's shutters. I don't have all that much to say about it, really. I mean, these were people getting paid to make comics, it's the best job in the world, they seemed to know that, and now those jobs are gone. That's about all that needs to be said about it.

The last 24 hours have seen an outpouring of sympathy and, I imagine, scorn over the folding of Wildstorm's shutters. I don't have all that much to say about it, really. I mean, these were people getting paid to make comics, it's the best job in the world, they seemed to know that, and now those jobs are gone. That's about all that needs to be said about it.But over at Heidi McDonald's Comics Beat, buried near the tail end of a long tribute to Wildstorm by various creators and staff over the years, is this beauty by Rob Lefield.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen felt as important as Watchmen, a return to Alan Moore’s penchant of taking existing icons and pulling them together in a massive sprawling epic. It made it to screen, complete with condemnation from Moore, faster than any of his previous works. Had the film been and performed better, it’s legacy would be even more immense. For me, the last great work of Alan Moore.

Now, for many, the very fact that Rob Liefeld wants to critique Alan Moore is laughable on its face. We are forced to ask the question, "What, pray tell, is the last great work of Rob Liefeld?" But that's not really fair in this case. Liefeld isn't writing about Alan as a critic, or even as a peer in the comics industry, but rather as a fan. Reading the rest of Liefeld's comments, his love for these books, his enthusiasm, his sheer envy and fan-geekery, are unhidden. And that is a perfectly legit forum for Rob Liefeld to critique Alan Moore. As a guy who reads Alan's books, and who likes them, and who happens to think that everything after the first volume of League has been downhill.

It's certainly true that since Moore started ABC, artists and editors have been desperate for anything he has written, even going to the extent to publish old songs and poems he wrote years before. You get some amazing artist to illustrate Alan's text, which was never meant to be a comic, and people are bound to buy it because, well, it's Alan Frikkin' Moore. And most of the time it is still worth it, but no one would claim that something like "Another Suburban Romance" or "Hypothetical Lizard" are Great Comics.

So if we eliminate the obvious noncontenders, what are we left with? Well, there's everything else at ABC, including Top Ten, Tom Strong, and Promethea, and there's Lost Girls.

I love Top Ten. I've used it in the classroom, teaching it in a freshman composition & literature course where we could focus on textual analysis. It was the last book in the quarter, and it was there for a reason, because of all the comics we read it was the hardest for the students to understand. Gene Ha's art was just so damn busy, so damn rich, that the students were overwhelmed at first. The layouts made them seasick. It was awesome, but took some getting used to. They loved the characters, the sheer gutsiness of the book. When my students realized that Kemlo was a dog with a human girlfriend, and they were going home to have sex, I mean ... those moments are priceless. What other writer would DO that? And, while doing it, make it clear that this wasn't just done for shock value. It actually humanized the characters. We felt kind of sorry for her, because her previous guys had been such dicks to her, and Kemlo was basically a human being in a dog suit. He was a guy who happened to be a doberman, and he wore his Hawaiian shirts, and he was the complete opposite of, for example, the robot police officer who came around in volume 2, who didn't want to be human because, well, that would have been a step down.

Top Ten was a great comic. But it wasn't a Great Comic. It is tragically cut short by its conclusion at the end of volume 2, or "Season One," with many plot threads left unresolved and so much left to do or say. But, really, as a police procedural, could it really have ended any other way? It ended the same way Law & Order ended, with a sudden end-of-season cancellation and a couple of spin-off books which are decent, solid, but wholly unremarkable imitations of the original. Now I can't stop thinking of Sam Waterson as Smax. Think about it. It could have worked.

I was slow to warm up to Tom Strong. I didn't get it at first, when the various ABC titles were first being marketed and hyped. I didn't realize it was a Doc Savage/Tarzan/everything else mash-up which speculated, "What would superheroes be like if Superman had never been invented?" That's a brilliant concept, and it uses a bunch of wonderful titles I adore from the pulp era and before. The age of Victorian adventure fiction got new life in Tom Strong, and if his stories were wild fun and a little bit kooky and far-out, well, that was the point. It had a talking ape and a robot man who used wax cylinders for a voice box, it had Nazi super-vixens and an auto-gyro, and everything in that sentence is made of win. There's no question Tom Strong was fun. But where it started to get great, when it started to be real, were those moments when Tom came face to face with his father, his mother, and his attitude towards these people. Tom's father imprisoned his son in a gravity well for his entire childhood in order to make him into a superman. And every time Tom was forced to confront the fact that he loved his father, but also resented him, the book saw greatness. Tom was a father and a husband, and though his battles with colossal cybernetic snakes from an alternate dimension were never really in doubt, his real struggle was to be a better man, a better husband, and a better father than his own father. And he longed to reconnect with his mother who was gone, in a way that any reader of Maus can instantly recognize. If Art Spiegelman and Tom Strong sat down for lunch together, you know they would instantly recognize each other.

I don't claim to be a Lost Girls expert. There are some people who have written long and thoughtful pieces on the book, people like Kate Laity or Emily Mattingly and others. I've got it, I read it, and I thought it was interesting, but I've never opened it back up since I finished it the first time. I remember I didn't really know what I was getting when I bought it. I pretty much picked it up because:

- It was Alan Moore

- He had been working on it for years

- It had literary characters in it

- It was porn

This four-punch combo was irrestible to me. And there's no question that the time, the sheer number of man-and-woman hours involved, is clear on every page. Gebbie has created something unlike anything else that is out there. And I am sure there is plenty in the text that I would appreciate, if I were educated on it. Issues of gender, and race, and sexuality, and machines and technology, and all kinds of other important topics. But the simple fact is that Lost Girls does not turn me on. Which I was pretty surprised about, to be honest. No matter what else we might get out of Lost Girls, it is written to be porn. Really, really, high quality porn. Porn that costs you a hundred dollars in hardcover and which you keep for a lifetime. But if porn does not turn you on, it's a failure. For those who are turned on by Lost Girls, bully for you. Don't let Christine O'Donnell catch you.

And what are we left with? Well, there's the other League books and there's Promethea. Did Liefeld mean to include the second volume of League and the Black Dossier and the stalled Century when he praised League as Alan's last great work? I don't know for sure, but I tend to doubt it. None of these comics have been made into film, which seems to be one of the measures by which Liefeld makes his case, nor have they been printed at Wildstorm, which seems to be what Rob is talking about here. But, out of caution, I will not try to argue that League volume 2 is Great, or that the Black Dossier is Great, despite my true and sincere admiration for both these books, which I have written about extensively elsewhere.And so, Promethea. She was an initial hit with readers, who saw in these pages an action-adventure comic with a strong female protagonist who didn't wear a thong. JH Williams III made this book into a transcendant masterpiece. The layouts, the gutter art, the design of the characters and everything else we saw told you that this, this, this was something worth reading. Something you would be talking about later. As the first story arc ended, people started to drift away from the book. Sophie started to wander the mystical universe, meeting a large cast of supporting characters drawn from history, occultism, and the imagination. She became a mouthpiece for exposition about how the cosmos was put together, how it worked. Or, rather, she asked all the questions, because she was the novice, the learner, and everyone else she encountered provided the answers. She was Dante and her guides were many. We began to learn what magic was. We learned its symbols and its voices. The book became impossibly dense. It experimented with art, with photo comics, with realism and cartoons. The book split into two different stories: Sophie continued her tour through the Sephiroth, walking the path of the magus, while her best friend became her rival back on Earth, kicking ass and taking names. But there wasn't enough ass-kicking for most readers, or for the comics media, who simply stopped reading. It became too high brow, even when the end came into sight and Alan suddenly reminded us that, oh yeah, Promethea looked like an Arab, which means she could be a Muslim terrorist, and the world we were living in, you and I, intruded into all that mystic mumbo-jumbo and reminded us that the cold equations are never far away.

Promethea is a Great Comic. It shoots higher than Tom Strong, than Top Ten, than Lost Girls. And it scores. It's not for everyone. It's never going to change the comic industry the way Watchmen did. And that means Rob Liefeld and the people like him are never going to love Promethea. That's because it does not speak to them. Those people are not its audience. Promethea speaks to the literati, to the student of history, of culture, to the magus and the aspiring magus. It reaches out to those of us who have read comics since we were six and it asks us, "Haven't you always thought there was something magical about comics?" And we quietly whisper, "Yes" where no one can hear us. Except Alan and Williams, who nod knowingly, pull back the curtain of the world, and usher us into the magnificant moon and serpent show of our dreams.

But even this, even this argument, is unfair. Because Alan Moore, despite his increasing grouchiness, is not yet done. I am not the first person to note that Moore has become increasingly ambivalent towards not only the comic industry, but even towards his fellow creators. I won't go into that here. But we know he has been working on a couple of major projects, and I for one am still hopeful that they will, someday, see the sun. One of those books is his novel, Jerusalem. Another is his grimoire in comic form. Will either of these two things be "Great"? I don't know, and maybe its just because I'm not a young man any more, but I would think twice before saying a creator like Alan Moore wrote his "last great work" over ten years ago, when the guy is still alive and still writing.

Saturday, September 11, 2010

Superhero Campaigns

I'm two-thirds of the way through my D&D4e campaign and everyone seems to be having a (mostly) good time, so it's not like I have any time to run anything else in the next, oh, year. But a casual remark by one of my players a month or so ago got me thinking that, if I were to run a new game, and if that game was a superhero game, what sort of game might I run?

I'm two-thirds of the way through my D&D4e campaign and everyone seems to be having a (mostly) good time, so it's not like I have any time to run anything else in the next, oh, year. But a casual remark by one of my players a month or so ago got me thinking that, if I were to run a new game, and if that game was a superhero game, what sort of game might I run?Thursday, September 9, 2010

Arthur Lives, Going Savage

So I have been spending my spare hours this week working on the Savage Worlds version of Arthur Lives. The two games are very different, not least because only one has classes and levels. True20 has a certain presumption of action-worthiness built into the system; your character cannot go up in level and be completely helpless, because your attack bonus, defense, and saves all go up with you. Yes, you could pick useless powers, and no doubt some players do that, put if you put a gun in the hand of a 16th level expert, even if that character has refused to acquire Firearm Proficiency, he'll still be practically invulnerable to low-level attackers and be able to shoot them dead.

So I have been spending my spare hours this week working on the Savage Worlds version of Arthur Lives. The two games are very different, not least because only one has classes and levels. True20 has a certain presumption of action-worthiness built into the system; your character cannot go up in level and be completely helpless, because your attack bonus, defense, and saves all go up with you. Yes, you could pick useless powers, and no doubt some players do that, put if you put a gun in the hand of a 16th level expert, even if that character has refused to acquire Firearm Proficiency, he'll still be practically invulnerable to low-level attackers and be able to shoot them dead.Saturday, September 4, 2010

Strictly Non-Aryan

Sometimes I stumble across images that grab me and make me write about them. This is one. It's from Look Magazine's 1940 two-page comic, "What if Superman Ended the War?", which you can read in its entirety here.

Sometimes I stumble across images that grab me and make me write about them. This is one. It's from Look Magazine's 1940 two-page comic, "What if Superman Ended the War?", which you can read in its entirety here.Monday, August 30, 2010

Cut Till it Hurts

I'm in the process of revising Superhero Comics and the Literature of the Middle Ages and Renaissance with an eye towards removing images I can live without. This will make my editor happy, which is a good thing, and might make it easier to get permissions, which is also a good thing. What's tough about this is that comics are about text and image, and my natural instinct whenever I am talking about a page is to show it to you, so I can just point and say, "See? See!" I wrote the Shakespeare/ Moore/ Claremont/ David chapter with knowledge of my image requirements in mind, and used far fewer than I otherwise would have, but when I was writing for my dissertation committee I didn't see any reason to hold back. Now I pay for that by making painful cuts. Every one of them makes the end result a less perfect book, but you just do what you can and hold your nose.

I'm in the process of revising Superhero Comics and the Literature of the Middle Ages and Renaissance with an eye towards removing images I can live without. This will make my editor happy, which is a good thing, and might make it easier to get permissions, which is also a good thing. What's tough about this is that comics are about text and image, and my natural instinct whenever I am talking about a page is to show it to you, so I can just point and say, "See? See!" I wrote the Shakespeare/ Moore/ Claremont/ David chapter with knowledge of my image requirements in mind, and used far fewer than I otherwise would have, but when I was writing for my dissertation committee I didn't see any reason to hold back. Now I pay for that by making painful cuts. Every one of them makes the end result a less perfect book, but you just do what you can and hold your nose.It would take only a nudge to make you like me. To push you out of the light.

Monday, August 23, 2010

7 Minutes to Midnight

- Going through the text for a final pass to remove any un-necessary illustrations, in order to make getting permissions easier.

- Working through Pete Coogan's Institute for Comic Studies to get my art permissions easily and quickly.

- Making a final pass through the notes and bibliography, to make sure everything has been included and cited.

Friday, August 13, 2010

Claremont's "Tempest": X-Men 147-150

[ This is quite long. But what the hell. ]

[ This is quite long. But what the hell. ]As we search for superhero comics that appropriate, re-enact, manipulate or comment on Shakespeare, it’s easy to restrict ourselves to those in which Shakespeare is actually quoted. “Tempest Fugit” throws us a lifeline of another sort; by making the title of the story into a pun on The Tempest, David sends up a signal that says, “Here there be Shakespeare.” (In case we did not yet notice, he also does quote the play’s most famous lines in a couple of places.) Similarly, characters are sometimes named after Shakespearean characters. When Aquaman’s former sidekick, Aqualad, grew up and became a wizard with magical control over the elements, he renamed himself Tempest. But the most famous use of Shakespeare in this sense is probably the sympathetic monster Caliban, created by Chris Claremont as part of his unforgettable seventeen year run writing The Uncanny X-Men. Although Caliban would remain a member of the X-Men mythos for decades, his first appearance in Uncanny X-Men #148 (August 1981) is the earliest stage of Claremont’s larger riff on “The Tempest”, which would last through issue #150.

“The nations of the world spend over a trillion dollars a year on armaments. I intend to deny them that indulgence. The money and energy devoted now to war will be turned instead to the eradication of hunger, disease, poverty. I offer a Golden Age, the like of which humanity has never imagined!”

“What about freedom?”

“Freedom, Ms. Forrester? There are more people starving today than there are those who can truly call themselves free. I offer peace and a good life … or a swift and terrible death. The choice is theirs.”Reading these stories today, when the United States is embroiled in two foreign wars and a simultaneous “Great Recession”, it is remarkably easy to see the logic in Magneto’s goals, if not his melodramatic means, and Claremont goes further when he establishes the reason for Magneto’s personal commitment to this seemingly impossible goal: he is himself a member of a repressed minority. Not just a mutant, Magneto is a Holocaust survivor. In words which could have come from Prospero himself, as he laments his exile from Milan, he tells Cyclops, “Search throughout my homeland, you will find none who bear my name. Mine was a large family, and it was slaughtered – without mercy, without remorse. So speak to me not of grief, boy. You know not the meaning of the word!” This is not the first mention Magneto will make of grief, a theme which the King of Naples and his wandering son often invoke as they each mourn the other, seemingly lost forever.

She – she is a child! What have I done?! Why did you resist? Why did you not understand?! Magda – my beloved wife – did not understand. When she saw me use my powers, she ran from me in terror. It did not matter that I was defending her…. That I was avenging our murdered daughter. I swore then that I would not rest ‘til I had created a world where my kind – mutants – could live free and safe and unafraid. Where such as you, little one, could be happy. Instead, I have slain you.This is Magneto’s great soliloquy moment, when he confesses to Kitty’s dead body that he has become a monster, the very thing he has all his life most hated. He laments his exile from his homeland, the death of his family, and how the need for revenge has burned in him since that day, in a way that Shakespeare’s Prospero eventually outgrew through a desire for reconciliation, happiness, and peace.

I remember my own childhood – the gas chambers at Auschwitz, the guards joking as they herded my family to their death. As our lives were nothing to them, so human lives became nothing to me. … I believed so much in my own destiny, in my own personal vision, that I was prepared to pay any price, make any sacrifice to achieve it. But I forgot the innocents who would suffer in the process. … In my zeal to remake the world, I have become much like those I have always hated and despised.This is, perhaps, Prospero as he might have been: not a man released by the forgiving heart of an audience after three hours of play, but instead a man whose “ending is despair,” bound by the conventions of his genre and the expectations of audience. Magneto cannot be freed because then the X-Men would lose their antagonist and the story would end. Periodically over the years writers have experimented with making Magneto turn himself in, be tried for his crimes, even join the X-Men or occasionally die; such moves are always ephemeral and temporary. Comics must be printed, writers and artists must be employed, t-shirts and video games must be sold, Hollywood blockbusters must be produced, millions of dollars must be made, and so the audience, while they may applaud, grant not freedom but further imprisonment, an endlessly extended sentence.